I received a message today—brief, yet carrying the weight of history.

“Hail. I’m a native of Akure, but my mother is from Okun. I wonder about two things in Kogi—when will a Christian rule, and when will Okun rule Kogi? Kogi is not a poor state. Thanks!”

I read it once. Then again. Not because the words were difficult, but because the truth within them was heavy. This was not just a question—it was an echo of generations of wounds, unfulfilled hopes, and a quiet reminder of the struggles many have whispered for years. It was not a demand for favouritism but a call for justice. And so, I write this response—not just for the one who sent the message but for every Okun sons and daughters who has ever asked the same question.

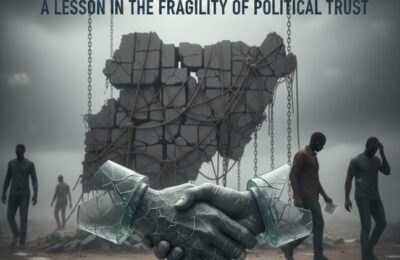

The river does not speak, but it remembers. It watches as men build empires along its banks, as fishermen cast their nets, as crocodiles glide beneath the surface, waiting. Kogi politics is like that river—deep, unpredictable, controlled by those who understand its currents. The Okun people have stood at the river’s edge for too long, watching as power flows past them, always nourishing the same lands while theirs remains dry.

Since Kogi State’s creation in 1991, the governorship has rotated between the Igala of Kogi East and the Ebira of Kogi Central. The Okun, despite their contributions to the state’s economy and political landscape, have never held the top seat. The same can be said of religious representation—Christians have occupied key positions but never the governorship. And so, the question remains: why?

It is not for lack of leadership. The Okun have produced some of Nigeria’s finest minds—thinkers, politicians, economists, and administrators. Nor is it about religious competence; Christians have led at the highest levels across Nigeria. The issue, instead, is political strategy. Power is never given; it is taken. Nelson Mandela once said, “It always seems impossible until it’s done.” But impossibility exists only for those who sit back and wait for power to be handed to them.

The crocodiles of Kogi politics do not wait. They move in groups, form alliances, and strike at the right moment. The Okun people must understand this if they hope to sit at the table of leadership.

Former Governor Yahaya Bello understood the game. He did not wait for power to find him; he pursued it with precision. And now, under Governor Usman Ododo, the empire he built remains intact. Power is not a guest—it is a house that must be built, brick by brick. Those who control the house do not give away the keys for free. If Okun must rule Kogi, if a Christian must sit on the throne, then the time for passive hope is over. It is time to build.

But there is an elephant in the room—disunity. The biggest obstacle for the Okun is not the Igala, nor the Ebira, nor even the political system. It is their own fragmentation. Okun politics is like a marketplace filled with voices shouting at the same time—everyone has an opinion, but no one listens. The elders say, “A single broomstick is weak, but a bundle is unbreakable.” If Okun truly wants power, it must move as one.

Unity, however, is not enough. Politics is about numbers. Kogi East has long dominated because of its larger voting population. If Okun seeks power, it must forge alliances—not as beggars, but as equal partners. The strongest hunters know that some animals require more than one spear. Politics is not a solo dance—it is a festival, and those who move together control the rhythm.

Then there is the issue of participation. Too many Okun sons and daughters have remained outside the political ring, watching from the sidelines, shaking their heads at the system but doing little to change it. A lion that refuses to roar cannot blame the forest for ignoring it. If Okun seeks the throne, it must fight for it—not with complaints, but with strategic action. Every election matters. Every vote counts. Power is not taken by those who merely analyze; it is taken by those who step forward.

But beyond political maneuvering, there is an even greater truth—Kogi is not poor. The state is blessed with untapped wealth—solid minerals buried beneath its soil, rivers capable of driving industrial growth, arable land that could feed millions. But potential alone does not bring prosperity. Leadership does.

A true leader is one who sees beyond immediate personal gain, one who understands that governance is not about eating today but about planting for tomorrow. A leader who recognizes that development is not a privilege but a right. The real question is not just when a Christian will rule, or when Okun will rule, but how leadership will be different when it finally happens.

Power, in itself, is not the goal—justice is. Competence is. The ability to transform Kogi into what it should be, rather than what it has been. When the rain falls, it does not choose one rooftop. The blessings of governance should reach every part of the state, not just a favored few. The next leader—whether Christian, Muslim, Okun, Igala, or Ebira—must understand this.

And so, to my brother from Akure, whose mother is from Okun, I say this: The future is not a gift; it is a responsibility. The dream of an Okun governor, of a Christian governor, is valid. But dreams alone do not shape history. It is time for Okun to rise—not through wishful thinking, but through unity, strategy, and action.

The crocodiles in Kogi politics will not step aside willingly. The question is—will the Okun people remain on the riverbanks, or will they wade into the waters and change the tide?

The river remembers. History records. And time waits for no one.

– Inah Boniface Ocholi writes from Ayah, Igalamela/Odolu

08152094428