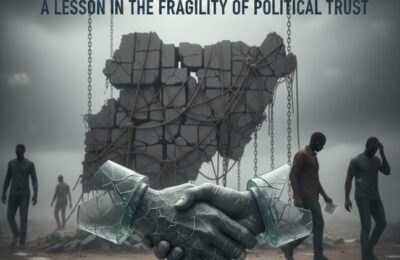

While nations like the United States advance technological boundaries with surgical precision, flying invisible bombers across continents for 37 uninterrupted hours—refueling midair, undetectable to enemy radars, hailed globally as “an engineering miracle”—Nigeria still wrestles with the basics of manufacturing tractors and grain processors. The B-2 Ghost Bomber, a stealth aircraft so sophisticated that it appears as a mere bird on radar—if it appears at all—has never been offered for sale to any country. It is not just a machine; it is a symbol of technological nationalism. America guards it jealously. It’s a sovereign tool of might, never up for diplomatic barter. The question remains: when will Nigeria create such engineering marvels not for global applause, but for internal empowerment?

It is tragic irony that a nation rich in brainpower and raw materials remains poor in purposeful invention. Nigerian inventors fabricate water-powered generators, mobile grain processors, and crude oil cleaning mechanisms, but their genius is either ignored, disvalued and most cases shipped off. In doing so, we sell the bread before feeding the hungry. “The future belongs to those who prepare for it today,” said Malcolm X. Yet, Nigeria’s preparation is outsourced; her future mortgaged to nations who respect and protect their inventors more than she does her own.

Nigeria is not lacking in ingenuity. What she lacks is the statecraft to harness, guard, and deploy innovation as a strategic tool of survival and supremacy. The B-2 Ghost Bomber is not being used for export revenues but for power assertion—proof that in the calculus of global politics, self-manufactured technology equals invincibility. Nigeria, meanwhile, continues to import toothpicks and celebrate refurbished machines from countries whose worst technicians would tremble before her best minds. “Wealth,” wrote Adam Smith, “is power.” But in the 21st century, wealth lies not just in money, but in machines.

The moral erosion of our engineering confidence stems from decades of policy betrayal and elite detachment. A machine built by a Nigerian is often discredited by the very society that birthed him. Local mechanics are good enough to repair imported vehicles, but not respected enough to build ours. Meanwhile, government contracts for industrial solutions are handed to foreign firms at premium costs. “No man is a prophet in his own land,” the saying goes—but must Nigeria make that a constitution?

Chinua Achebe, Nigeria’s literary seer, warned that “the trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership.” But in this context, it’s also a failure of vision. Our nation remains in love with foreign tools and suspicious of homegrown brilliance. The universities teach theories, not practicals. The polytechnics are sidelined. The street inventors are dismissed. Yet the greatest inventions of our time did not emerge from ivory towers, but from gritty garages and lonely nights of experimentation. Think of Thomas Edison. Think of the Wright brothers. Think of Elon Musk. Then ask: where are Nigeria’s equivalents? Probably in a roadside workshop—underfunded, underrated, and unseen.

There must arise a policy revolution—a decisive ideological U-turn that mandates: no indigenous machine must be exported before serving the nation. Just as America refuses to sell the B-2 Ghost Bomber, Nigeria must protect her engineering miracles. Let the world see our machines in action in Nigeria before they desire them abroad. Let our tractors till our fields, our drones monitor our borders, and our processors revive our agro-economy. “Necessity,” said Plato, “is the mother of invention.” Nigeria is in need. She must give birth to her own solutions—and raise them to maturity before putting them up for adoption.

We cannot afford to repeat the post-colonial error of resource exportation without local beneficiation. The same way we exported crude oil and imported refined petrol, we now risk exporting minds and importing manufactured goods. If we must rise, it must be with a firm grasp of national industrial pride. Let our inventors know that their country is their first customer, not their last.

When Nigeria builds her own version of the Ghost Bomber—not necessarily for war, but for peace, agriculture, surveillance, and industrialization—and reserves it solely for national use, only then will the world respect our technological sovereignty. Until then, we are like a man who built a golden mansion but sleeps in the rain.

– Inah Boniface Ocholi writes from Ayah – Igalamela/Odolu LGA, Kogi state.

08152094428 (SMS Only)