During the week, my colleague whose brother is a barrister visited, and we got talking. After a brief introduction, he smiled and said it would be interesting to see me in court someday as a learned colleague. But that was by the side. As an avid listener and learner though with a background in law; I asked him a question that has long lingered in my mind: Why do many Nigerians believe the judiciary is responsible for the country’s woes?

His response was both historical and thought-provoking. He traced Nigeria’s troubles back to 1914 when the Northern and Southern Protectorates were amalgamated. According to him, the union was premature; forced together without genuine consideration for the deep ethnic, cultural and religious differences that defined the people. He explained that Nigeria’s independence in 1960 came too easily, “on a platter of gold,” and because the struggle lacked the collective sacrifice and shared pain seen in some other African countries, our sense of unity was never truly forged. He argued that if our early leaders had faced the same harsh realities of imprisonment and oppression; regardless of tribe or status like the case of Ghana or South Africa, perhaps the “inconsiderable feelings” that divide us today might have been less severe.

As our conversation deepened, he quoted the late Justice Chukwudifu Oputa, a renowned Justice of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, who once said: “Judges are not infallible; they are human and therefore fallible.” That line, he said, sums up the reality of the judiciary; flawed not because it lacks good minds, but because it operates within a system that often compromises its independence. He stressed that Nigeria’s problem is no longer just about individuals; it is systemic, entrenched in the very structure of governance.

He then pointed to Section 308 of the 1999 Constitution (as amended); the provision that grants sitting Presidents, Vice Presidents, Governors and Deputy Governors immunity from civil or criminal prosecution while in office. “That single section,” he argued, “is both a shield and a sword. It protects those in power from accountability and weakens the very foundation of justice.” He maintained that as long as that immunity clause remains, corruption and abuse of office will continue unchecked and no meaningful reform can truly take root.

Listening to him, I couldn’t help but agree. Our challenges are not born of ignorance but of design, carefully built into a system that shields the powerful and burdens the powerless. Until we summon the courage to reform both the structure and spirit of governance, Nigeria will remain trapped in a loop where justice is delayed, denied, or distorted. Indeed, the Barrister Ezekiel was right: for Nigeria to work again, the law must first be free to serve everyone equally.

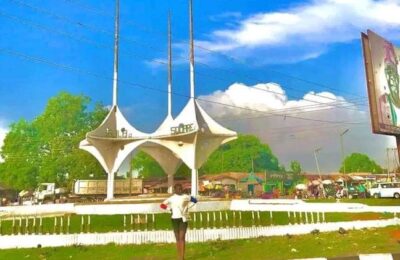

– BinMaLik writes from Lokoja.