The most unsettling idea in Christianity is not heaven, hell, or judgment. It is the claim that God allowed Himself to be broken. In a world that equates strength with domination and leadership with control, the image of a wounded God hanging on a cross remains a moral provocation. Two thousand years on, it still refuses to fit neatly into politics, culture, or modern religion.

At the centre of the Christian faith is not a throne but a cross. Not a show of force but an act of surrender. The Gospel of Isaiah anticipated it with brutal clarity: “He was despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3). This was not symbolic language. It was a warning. God would confront human evil not by overpowering it but by absorbing it.

This pentagon of power explains why Christianity has always been uncomfortable for empires. Rome understood strength. It did not understand mercy. Yet while Caesar’s statues lie broken in museums, the cross still stands, quietly indicting every system built on fear. As the Apostle Paul put it, “The message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God” (1 Corinthians 1:18).

The broken God overturns human logic. Nations rise by conquest, markets grow by extraction, leaders rule by intimidation. But the Christian God rules by self-giving. Jesus’ words remain politically explosive: “The rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them… Not so with you” (Matthew 20:25–26). Power, in this framework, is not proven by how much pain one can inflict, but by how much one is willing to carry.

This is not sentimental faith. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, executed by the Nazis, warned against cheap religion, insisting, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die.” The broken God does not offer escape from suffering but meaning within it. He does not promise comfort without cost. He promises redemption through obedience, sacrifice, and truth.

Modern Christianity often struggles with this. There is a growing preference for a triumphant God who blesses ambition and shields believers from discomfort. Yet the Jesus of the Gospels refuses to be weaponised. He weeps, bleeds, and forgives. On the cross, He prays not for revenge but for mercy: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). No political ideology has ever survived such a sentence unchallenged.

The resurrection does not cancel the brokenness. It confirms it. The risen Christ still bears scars. Thomas is invited to touch them. Glory does not erase suffering; it redeems it. As St Augustine observed, “God had one Son on earth without sin, but never one without suffering.” The wounds remain as evidence that love, not violence, has the final word.

In fractured societies, this matters. The broken God stands closer to refugees than rulers, closer to prisons than palaces, closer to the marginalised than the celebrated. He is found where hope seems unreasonable. As the Psalmist writes, “The Lord is near to the brokenhearted and saves the crushed in spirit” (Psalm 34:18).

The cross is not a relic of ancient belief. It is a mirror held up to every generation. It asks uncomfortable questions: What kind of power do we trust? What kind of strength do we admire? What kind of God do we want?

The broken God does not dominate history by force. He haunts it with conscience. And until humanity learns that true authority kneels before it commands, the cross will remain the most radical symbol the world has ever known.

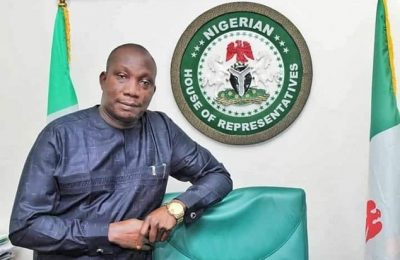

– Inah Boniface Ocholi writes from Ayah – Igalamela/Odolu LGA, Kogi state.

08152094428 (SMS Only)