In a nation already bruised by insecurity, economic paralysis, and institutional decay, the shock was not that things had fallen apart; but that a senior Nigerian statesman finally said the quiet part aloud: maybe Britain should come back. His words, jarring in their bluntness, pierce through the national pretense like a knife through thin cloth. When an elder who once defended Nigeria’s sovereignty now mutters re-colonisation as a solution, it signals not controversy but collapse. It is the political equivalent of a patient calling the undertaker instead of the doctor.

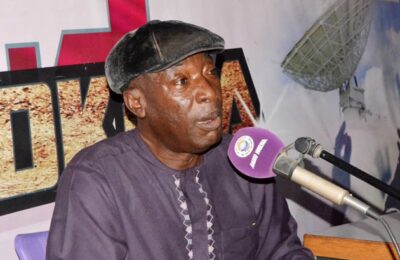

Buba Galadima’s remarks are more than frustration; they are a grim metaphor for a republic drifting without a compass. His cry resembles Fela’s eternal lamentation “Suffering and Smiling” a people enduring torment with forced laughter, clutching their misery like a rosary. Nigeria today is a theatre where the actors have forgotten the script, the director has gone missing, and the audience has grown too exhausted to protest the chaos on stage. It is in this vacuum of leadership and meaning that the unthinkable becomes thinkable: the return of the colonial master.

The irony is bitter. A nation that once danced to the jubilant drums of independence now stands like a broken masquerade, costume torn, spirit dispirited, begging for the very whip it once rejected. Galadima’s imagery of bandits capable of riding into Abuja unchecked, reads like a pregnant woman having political nightmare. In the fields where food should grow, fear now germinates faster than crops. Even the simple act of farming has become a gamble between hunger and death. These are not the exaggerations of an alarmist; they are the lived experiences of millions trapped in a system where governance has become a ghost story told at dusk.

The deeper tragedy is that such desperation does not arise from sudden disaster but from the slow corrosion of institutions over decades. Vote-buying has transformed elections into auctions. Security has mutated into a lottery. Agriculture has been abandoned for import pipelines that enrich the few while impoverishing the many. Nigeria’s leaders have become maestros of dysfunction, conducting an orchestra of chaos with practiced indifference. And like Fela warned in “Beast of No Nation,” the country has become a place “where the truth has no home,” forcing critics to become seers and patriots to sound like heretics.

Yet the call for recolonisation is not a solution; only a symptom. It is also an insults to many intelligent and brilliant Nigerian youth out there.

Infact, it is the final cry of a people who feel cornered by their own republic, trapped in a nation that seems determined to sabotage its own survival. No foreign flag can heal the wounds inflicted by domestic negligence. Nigeria’s redemption will not arrive on a British ship but in the moral revolt of its own citizens, the resurrection of public accountability, and the restoration of a social contract long abandoned. Until then, the nation will continue, like Fela’s lyrics foretell, suffering, smiling, and sinking, while elders whisper options that once would have been unthinkable for a proud people.

– Inah Boniface Ocholi writes from Ayah – Igalamela/Odolu LGA, Kogi state.

08152094428 (SMS Only)