By Musa Tanimu Nasidi.

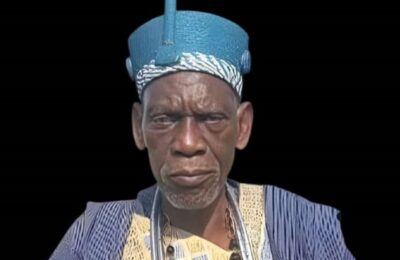

The appointment of Abubakar Rajab, widely regarded as an Islamic cleric, as Chairman of the Kogi State Lottery Board has sparked debate that goes beyond politics and governance.

At its core lies a deeper question: how should Islamic scholars navigate public office when state institutions conflict with clear religious teachings?

Lottery is not merely a revenue mechanism under Nigerian law; it is, by definition, a game of chance.

In Islam, such activities fall squarely under maysir (gambling), a practice the Qur’an explicitly prohibits. Allah states:

“O you who believe! Intoxicants, gambling (maysir), sacrificing on stone altars, and divination by arrows are an abomination of Satan’s handiwork. So avoid them that you may be successful.”

(Qur’an 5:90)

The prohibition is not arbitrary.

The Qur’an further explains the moral and social consequences of gambling:

“Satan only seeks to cause between you animosity and hatred through intoxicants and gambling, and to turn you away from the remembrance of Allah and from prayer.”

(Qur’an 5:91)

Classical and contemporary Islamic scholars agree that modern lotteries—where participants stake money for a chance to win larger sums—fit this description.

Wealth is transferred not through labour or trade, but through chance, with gain dependent on another’s loss.

As such, buying lottery tickets, profiting from them, or promoting them is widely regarded as haram.

This consensus places Islamic clerics in a uniquely sensitive position. Clerics are not ordinary public figures; they are viewed as custodians of moral guidance.

Their actions, appointments and affiliations often carry symbolic weight. When a cleric assumes leadership of an institution directly tied to gambling, it raises concerns about moral coherence and public perception.

The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) underscored the seriousness of gambling-related conduct when he said:

“Whoever says to his companion, ‘Come, let us gamble,’ must give charity.”

(Sahih al-Bukhari; Sahih Muslim)

Scholars note that if merely inviting someone to gamble attracts moral consequence, then overseeing a gambling institution raises even greater ethical questions.

Islam also lays emphasis on the purity of earnings. The Prophet (peace be upon him) said:

“Indeed Allah is Pure, and He accepts only what is pure.”

(Sahih Muslim)

This principle has long guided jurists in warning against occupations that are built on unlawful income. While serving in government is not inherently problematic, direct involvement in administering prohibited activities remains a red line in mainstream Islamic thought.

The Qur’an further places responsibility on religious scholars to uphold moral clarity:

“Why do the rabbis and religious scholars not forbid them from sinful speech and unlawful consumption?”

(Qur’an 5:63)

This verse is frequently cited to remind scholars that leadership is not limited to sermons; it includes conduct, silence and participation. A cleric’s acceptance of certain roles may unintentionally legitimise what Islam forbids, particularly in the eyes of followers who look to scholars for guidance.

Some argue that in a plural society, a Muslim can serve in any public office without endorsing its moral foundations. Others suggest that such appointments are administrative rather than religious.

While these arguments exist, the dominant scholarly position advises avoidance of doubtful matters, especially for those whose identity is rooted in religious authority.

The Prophet (peace be upon him) warned:

“Whoever sets a bad precedent in Islam will bear its burden and the burden of those who act upon it.”

(Sahih Muslim)

Ultimately, the controversy surrounding Abubakar Rajab’s appointment is not about legality but moral consistency.

It highlights the ongoing tension between governance and faith in a modern state. For Islamic scholars in public life, the challenge remains how to serve society without compromising principles that define their spiritual authority.

In Islam, leadership is trust (amanah), and where the Qur’an and Sunnah speak clearly, scholars are expected to tread with caution.

– Musa Tanimu Nasidi is a journalist and publisher of THEANALYSTMEDIA. He writes from Lokoja, Kogi state