The cries for Okura State are no longer whispers in the dark corridors of failed federal promises; they are roaring chants from a people whose liver fire has simmered for decades under the weight of marginalization. The call is not secessionist, nor does it echo ethnic vendetta — it is a constitutional and historical reclamation of political dignity, development, and regional equity. The political consciousness in Igalaland has matured into an awakening that neither temporal alliances nor rhetorical pacification can quench.

The quest for the creation of Okura State is not a recent brainstorm fueled by ephemeral discontent; it is an agelong desire encoded in the political DNA of the Igala nation. From the twilight of the Kwara era to the abortive dream of Benue, and eventually to the reluctant entanglement with Okun and Ebira in Kogi State, the Igala people have continually deferred their rightful political destiny. The geo-political transitions have been more of convenience than justice — a pattern of administrative shuffling that left the Igala heartland with peripheral influence despite their numerical dominance and historical relevance.

The creation of Kogi State was never the fulfillment of Igala political aspirations; rather, it was the dilution of their ancestral claim into a tripartite coalition where their political relevance has been systematically neutralized. What began as an opportunistic federal structuring has since mutated into structural imbalance, chronic underdevelopment, and political alienation. The liver fire that now burns in Igala consciousness is, therefore, not a spontaneous combustion — it is the cumulative anger of a people made peripheral in their own homeland.

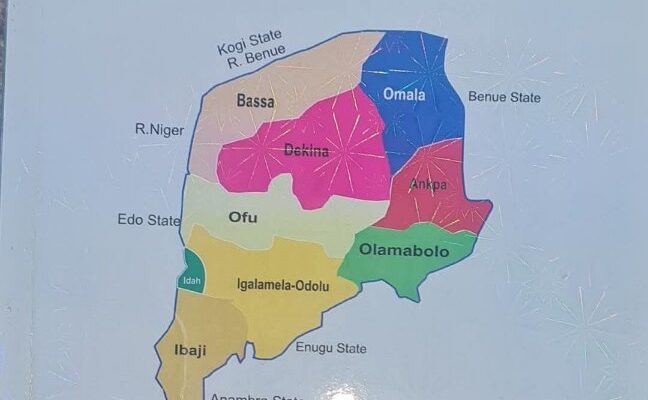

Leftist political philosophy contends that development is not merely the presence of infrastructure but the decentralization of power for the equitable distribution of opportunity. Okura State is not a selfish dream but a pragmatic pursuit to dismantle political overcentralization and redirect national resources to historically neglected terrains. The creation of 24 local government areas, three senatorial districts, and an expanded House of Representatives configuration will not only serve the Igala people — it will catalyze regional integration, job creation, and infrastructural rebirth in line with the original tenets of federalism.

One must underscore that the agitation is not birthed in rebellion, nor is it an exodus from Kogi State. The Igala people are not fleeing from coexistence; they are confronting a political architecture that has rendered them docile participants in a game they once captained. The liver fire metaphor here becomes symbolic — not of rage, but of a burning insistence for dignity and equal stake in the Nigerian project. It is the same fire that birthed states like Ebonyi, Bayelsa, and Ekiti — regions that are now vibrant testaments to what decentralized governance can achieve.

Opponents of Okura State often brandish fears of fragmentation, yet fail to acknowledge that unity without justice is nothing but a decorative tyranny. The blueprint for a more functional Nigeria lies not in suppressing internal agitations but in recognizing and restructuring around them. When people clamor for self-actualization within the framework of the constitution, it is not a threat to the union but a lifeline to its survival. Okura State, if birthed, will be an emblem of restored confidence in Nigeria’s commitment to true federalism.

Politically, the implications are profound. A new state realigns voting strength, redistributes federal allocations, and repositions minority voices in national debates. It also reconfigures senatorial representation and breaks oligarchic patterns that have monopolized development for select regions. Okura State would not just be a geographical entity; it would be a socio-political renaissance — a beacon of equitable representation in a federation often blurred by demographic prejudice and ethnic arithmetic.

Ultimately, the quest for Okura is a testament to the fire that still burns in the liver of the Igala nation — a fire neither waterlogged by political disappointments nor extinguished by administrative trickery. It is a moral question now turned constitutional. For too long, the Igala people have been passengers in a train they helped build. It is time they steered the engine. Okura State is not just a demand; it is a declaration that every part of Nigeria deserves the dignity of self-governance, the right to development, and the fire to define their destiny.

– Inah Boniface Ocholi writes from Ayah – Igalamela/Odolu LGA, Kogi state.

08152094428 (SMS Only)