There is no easy way to begin a story like this. You pick your words, then drop the pen, then pick it up again, struggling not with what to write but how to write it without losing your humanity.

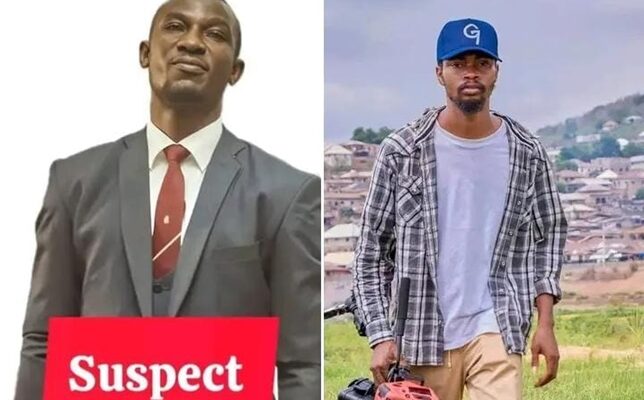

Ayo Aiyepeku, a young man, full of life, full of promise, carrying cameras instead of guns, dreams instead of daggers, is said to have been lured, murdered, packed like moinmoin into a freezer, and transported in a Hilux van as though he were some meat from the slaughterhouse.

And the man accused of this horror? Oluwapelumi Tolani Simidele Adebayo, a uniformed official of the Nigerian Correctional Service, a so-called custodian of order. A man whose job was to keep criminals away from society, now accused of becoming the very monster he was paid to restrain.

But this is Nigeria. So even this horror, this utterly insane, demon-dripping tale of ritual suspicion, body trafficking, and suicide with Sniper and Coca-Cola, finds room under the canopy of things we are forced to normalize.

Even murder has developed a pattern. And in our usual way, we are expected to move on. But how?

There was a chase. A dramatic manhunt through Lokoja’s streets, involving security agents, vigilantes, commercial motorcyclists, and concerned citizens. In that rare moment of unity, the people showed the state what real outrage looks like. They gave it a name. Justice.

But then came the twist, like every Nigerian tragedy, soaked in ambiguity. The alleged murderer, Pelumi, vanished into the bush near River Niger, only to resurface inside a hotel room. Dead. Naked. Alone. With Sniper, biscuit, and a note.

He wrote that his son should not be told what he did.

Let us pause and ask: What did he mean by that?

Did he suddenly grow a conscience between the bush and the hotel? How did he return to town unnoticed? Where did he get the suicide supplies? Who brought them? Why was he naked? Where is the CCTV footage of the hotel? Did someone visit him there? Why did no staff raise alarm when a man in distress walked?

And most importantly, where is Ayo’s body?

And crucially, where is his phone?

The mobile phone of a man on the run, who just committed murder, is a goldmine of evidence. It should be in the custody of the police or tracked through telecom providers. If it has disappeared, then we are not just dealing with a crime, we are dealing with a sophisticated erasure.

These questions are not for decoration. They are pillars of justice. If not answered, what we are building is not a society but a slaughterhouse.

The excuse in the suicide note was “Impulse Disease.” What does that mean? Is it a clinical diagnosis or a literary alibi?

A man kills another, freezes him like fish, loads the body into a van, evades arrest using stunt moves worthy of a Nollywood award, and then blames “impulse”? Is that even believable?

An impulsive person doesn’t clean up a crime scene. An impulsive person doesn’t leave a note.

But we’re being told he did.

Then again, even in death, Pelumi continues to insult the intelligence of the living. He remembered his son. But he forgot Ayo. He forgot to mention what happened to the boy whose life he cut short. He forgot the names of the people he may have been working for. He forgot the crime scene he left behind. He forgot the country that needed answers.

The silence in his note is deafening, and suspicious.

Where Is Ayo?

This is not a rhetorical question.

Was it dumped in the river? Sold for body parts? Collected by another player in this sordid story? Is Kogi now an unsuspecting hub in Nigeria’s unspoken organ trade?

The fact that this question has not produced an immediate, credible answer is itself an indictment.

Pelumi’s death has only added darkness to an already black narrative. He did not give justice. He gave us more questions. And in Nigeria, questions are often where justice dies.

Let’s backtrack. This is not just about Ayo. It is about how easily evil blends into the fabric of everyday Nigeria.

A man, uniformed, trained, salaried by the state, reportedly harbored darkness so thick it swallowed a fellow human being, and yet nobody noticed until it was too late. Nobody suspected. Or did they?

Was this his first? Or just the first to be caught? Are there others, buried, dumped, lost? Is there a syndicate? Did someone tell him to fetch human body parts? Where were they to be delivered?

What was the freezer doing in the van? Who helped him load it? Does a killer plan a logistics route without accomplices?

We are being asked to believe a lone wolf narrative in a system that breeds criminal packs.

And what of Ayo? Where is his body? A mother bought by grief is selling nothing anymore, not moinmoin, not smiles, not hope.

How does a mother mourn a son whose body she cannot see, touch, or bury?

This woman is one of us. The pain is not hers alone. When one child becomes meat in a freezer, we are all cooked.

But has anyone asked the most important question: Will Ayo get justice?

Real justice, not a media update. Not a photo op. Not the illusion of movement in place of meaning.

We have seen this before. We know how it ends.

The theatre opens, the actors perform, and then the lights go off, until the next victim. Because in Nigeria, death is rarely the end. It is usually the beginning of cover-ups, silence, and power games.

The killer dies, and so does the case. The boy disappears, and so does the truth.

In other societies, the freezer would be examined by forensic experts. DNA traces would be collected. Phone records would be extracted. Hotel camera footage would be subpoenaed. The hotel manager, front desk, and cleaning staff would be taken in for questioning.

His bank accounts would be frozen. Every chat, call, transaction, and location ping would be examined.

But here? We bury the truth faster than the dead.

The worst part is not just that evil happened. It is that it happened in daylight, in full view of a society desensitized to its own decay.

We debate the grammar of the suicide note while a family waits to bury their son. We worry whether Pelumi left a final clue while Ayo’s body is still missing.

We say “God will judge” because man has refused to judge. We say “justice must be served,” yet we watch as the case is wrapped in a blanket of excuses.

This is not normal. And the danger is that we are normalizing it.

A boy is dead.

Another man is dead, and the answers he took to the grave might have been our only truth.

And a society is standing between truth and forgetfulness.

Will Ayo ever get justice?

Or will he become just another file, another freezer story?

That, dear Nigerians, is the question.

– Adeyemi Babarinde Sunday writes from Kogi state.