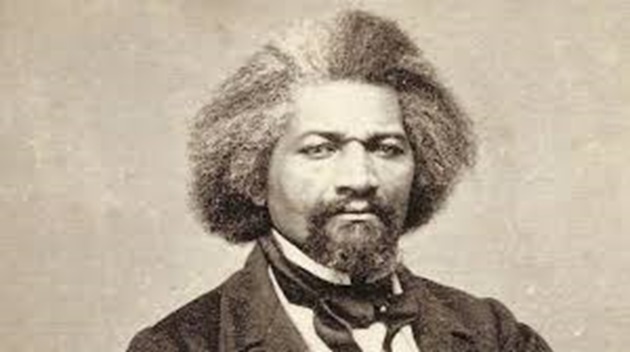

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey; c. February 1817 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, becoming famous for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings. Accordingly, he was described by abolitionists in his time as a living counterexample to slaveholders’ arguments that slaves lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.

Douglass was separated from his mother at infancy and he lived on after with his maternal grandmother, Betsy Bailey who was also a slave and his maternal grandfather, Isaac who was free. Frederick’s mother remained on the plantation about 12 miles (19 km) away, only visiting Frederick a few times before her death when he was 7 years old. Douglass was of mixed race, which likely included Native American and African on his mother’s side, as well as European.

At the age of 6, Frederick was separated from his grandparents and moved to the Wye House plantation and was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld, who sent him to serve Thomas’ brother Hugh Auld in Baltimore. When Douglass was about 12, Hugh Auld’s wife Sophia began teaching him the alphabet.

From the day he arrived, she saw to it that Douglass was properly fed and clothed, and that he slept in a bed with sheets and a blanket. Douglass described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman, who treated him “as she supposed one human being ought to treat another.” Douglass secretly continued to teach himself and also learned to read and write from the white children in the neighbourhood.

When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he taught other slaves on the plantation to read the New Testament at a weekly Sunday school. In 1833, Thomas Auld took Douglass back from Hugh and sent him to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a “slave-breaker”. He whipped Douglass so frequently that his wounds had little time to heal. The 16-year-old Douglass finally rebelled against the beatings, however, and fought back. After Douglass won a physical confrontation, Covey never tried to beat him again.

Douglass first tried to escape from Freeland, who had hired him from his owner, but was unsuccessful. In 1837, Douglass met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman in Baltimore about five years his senior. Murray encouraged him and supported his efforts by aid and money. On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped by boarding a northbound train of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad and went to the safe house of noted abolitionist David Ruggles in New York City. His entire journey to freedom took less than 24 hours. Douglass and Murray got married eleven days after he arrived New York.

The couple later settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts and he became a preacher and an abolitionist. After Douglass’s freedom, he wrote several abolition newspapers, supported the women suffrage, black suffrage and the end of slavery.

Douglass was appointed president of the Reconstruction-era Freedman’s Savings Bank. In 1872, Douglass became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States, as Victoria Woodhull’s running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket. Douglass became the first person of colour to be named as United States Marshal for the District of Columbia,

Douglass and Anna Murray had five children: Rosetta Douglass, Lewis Henry Douglass, Frederick Douglass Jr., Charles Remond Douglass, and Annie Douglass (died at the age of ten). After Anna died in 1882, in 1884 Douglass married again, to Helen Pitts, a white suffragist and abolitionist from Honeoye, New York.

Douglass wrote three autobiographies, notably describing his experiences as a slave in his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), which became a bestseller, and was influential in promoting the cause of abolition, as was his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855).

Following the Civil War, Douglass remained an active campaigner against slavery and he wrote his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. First published in 1881 and revised in 1892, three years before his death, the book covers events both during and after the Civil War. Douglass also actively supported women’s suffrage, and held several public offices. Without his permission, Douglass became the first African-American nominated for Vice President of the United States as the running mate and Vice Presidential nominee of Victoria Woodhull, on the Equal Rights Party ticket.

Douglass believed in dialogue and in making alliances across racial and ideological divides, as well as in the liberal values of the U.S. Constitution. When radical abolitionists, under the motto “No Union with Slaveholders”, criticized Douglass’ willingness to engage in dialogue with slave owners, he replied: “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.”

Douglass spoke out against the separatist movements, urging blacks to stick it out. He made similar speeches as early as 1879, and was criticized both by fellow leaders and some audiences, who even booed him for this position. Speaking in Baltimore in 1894, Douglass said, “I hope and trust all will come out right in the end, but the immediate future looks dark and troubled. I cannot shut my eyes to the ugly facts before me.”

President Harrison appointed Douglass as the United States’s minister resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti and Chargé d’affaires for Santo Domingo in 1889. but Douglass resigned the commission in July 1891 when it became apparent that the American President was intent upon gaining permanent access to Haitian territory regardless of that country’s desires. In 1892, Haiti made Douglass a co-commissioner of its pavilion at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

In 1892, Douglass constructed rental housing for blacks, now known as Douglass Place, in the Fells Point area of Baltimore. The complex still exists, and in 2003 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In Douglass’ final years, the Freedman’s Savings Bank went bankrupt on June 29, 1874, just a few months after Douglass became its president in late March. During that same economic crisis, his final newspaper, The New National Era, failed in September. When Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was elected president, he named Douglass as United States Marshal for the District of Columbia, the first person of color to be so named. The Senate voted to confirm him on March 17, 1877. Douglass accepted the appoint, which helped assure his family’s financial security. During his tenure, Douglass was urged by his supporters to resign from his commission, since he was never asked to introduce visiting foreign dignitaries to the President, which is one of the usual duties of that post. However, Douglass believed that no covert racism was implied by the omission, and stated that he was always warmly welcomed in presidential circles.

In 1877, Douglass visited Thomas Auld on his deathbed, and the two men reconciled. Douglass had met Auld’s daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, some years prior; she had requested the meeting and had subsequently attended and cheered one of Douglass’ speeches. Her father complimented her for reaching out to Douglass. The visit also appears to have brought closure to Douglass, although some criticized his effort.

That same year, Douglass bought the house that was to be the family’s final home in Washington, D.C., on a hill above the Anacostia River. He and Anna named it Cedar Hill (also spelled CedarHill). They expanded the house from 14 to 21 rooms, and included a china closet. One year later, Douglass purchased adjoining lots and expanded the property to 15 acres (61,000 m2). The home is now preserved as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

Douglass has received numerous honours all over the globe some of which includes: ▪ In 1899, a statue of Frederick Douglass was unveiled in Rochester, New York, making Douglass the first African-American to be so memorialized in the country.

▪ In 1921, members of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity (the first African-American intercollegiate fraternity) designated Frederick Douglass as an honorary member. Douglass thus became the only man to receive an honorary membership posthumously.

▪ The Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge, sometimes referred to as the South Capitol Street Bridge, just south of the US Capitol in Washington, D.C., was built in 1950 and named in his honor.

▪ In 1962, his home in Anacostia (Washington, D.C.) became part of the National Park System, and in 1988 was designated the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

▪ In 1965, the United States Postal Service honored Douglass with a stamp in the Prominent Americans series. In 1999, Yale University established the Frederick Douglass Book Prize for works in the history of slavery and abolition, in his honor. The annual $25,000 prize is administered by the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History and the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale.

▪ In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Frederick Douglass to his list of 100 Greatest African Americans, etc.

“Biography of Fredrick Douglass”; A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, 1845; My Bondage and My Freedom (second autobiography), 1855; Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (third and final autobiography), 1881 (revised 1892); “How Slavery Affected African American Families”. National Humanities Center. n.d. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012; “Resistance to the Segregation of Public Transportation in the Early 1840s”. primaryresearch. org. March 10, 2009. Archived from the original on August 6, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

– Sunday Johnson Onoruoiza

300 Level, Mass Communication Department,

Prince Abubakar Audu University, Anyigba, Kogi State.