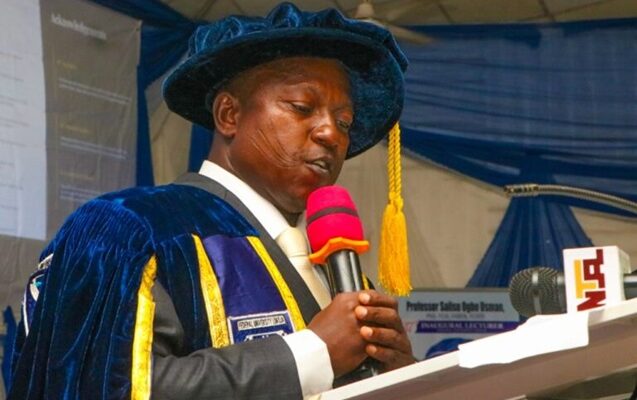

On Tuesday, 14th January, 2026, I witnessed a historic intellectual harvest at the Federal University Lokoja: the 37th Inaugural Lecture delivered by Professor Salisu Ogbo Usman.

Titled “Corruption Versus Corruption: Unpacking the Wuru-Wuru of the Anti-Corruption Crusade in Nigeria,” the lecture was a bold and unflinching autopsy of the Nigerian state. It reflected the depth of scholarship of a seasoned academic who has spent decades interrogating the nexus between power, resources and marginalization.

As mentee, reviewing this lecture is both an academic journey through a scholarly magnum opus and an engagement with what may be described as a socio-political manifesto.

I followed and subsequently read in detail the entire 74-pages presentation carefully and attentively, fully aware that this was far more than a statutory academic exercise; it was a carefully constructed moral manifesto that explains why Nigeria’s anti-corruption efforts often resemble a futile chase after shadows.

Prof. Usman’s central academic contribution lies in his deconstruction of “anti-corruption” itself as a potentially corrupt enterprise. He elevates “wuru-wuru”; a term drawn from Yoruba street parlance into a formal political concept, using it to describe the deceptive, selective and manipulative character of Nigeria’s performative governance.

He contends that the Nigerian state operates within a vicious cycle where corruption ostensibly “fights” corruption. This contradiction is illustrated through his Pyramids of Corruption model, which exposes a painful paradox: although anti-corruption laws claim to serve the public interest, elite private interests often determine which cases are pursued and which are quietly abandoned or resolved through plea bargains that protect “sacred cows.”

Central to his thesis is the application of the Resource Curse Theory and the Dutch Disease. Prof. Usman offers a rigorous explanation of Nigeria’s persistent economic stagnation, attributing the “Paradox of Plenty” to the country’s rentier-state structure. Dependence on unearned oil revenue, he argues, weakens government accountability to citizens whilst intensifying competition among elites for control of oil rents.

He further distinguishes between point and diffuse resources, noting that corruption thrives more aggressively in sectors such as oil and gas; point resources that are easily monopolized by a small elite. This structural condition has nurtured a pervasive “get-rich-quick” mentality that cascades from high-ranking “pen robbers” to artisans, traders and ordinary citizens.

One of the most compelling moments of the lecture was his treatment of the Ajaokuta Steel Company as a case study in systemic failure. Rather than merely labeling it a failed project, Prof. Usman describes it as a “conduit of corruption” and just as Achebe described it as “white elephant projects” which serves as a haunting reminder of how systemic corruption manifests in the physical landscape of the nation, stagnating industrial growth.

In a provocative suggestion by a commentator that it be converted into a National Museum of Shame by a commentator with evidence of decades of wuru-wuru governance; billions expended without a single sheet of steel produced. For him, Ajaokuta stands as a grim monument to how corruption scars both the economy and the physical landscape of the nation.

Departing from conventional academic caution, Prof. Usman proposed a radical “Way Forward” by advocating the “death penalty” for corruption. He defends this position by classifying corruption as a mass-casualty crime: when public funds meant for hospitals are looted and patients die as a result, the act, in effect, constitutes murder.

He also critiques the reliance on religious texts during oath-taking ceremonies, arguing that they defer punishment to the afterlife. In contrast, he suggests that African traditional oath-taking systems known for their immediacy of consequences may offer stronger deterrence in a leadership environment increasingly devoid of the “fear of God.”

Prof. Usman was equally unsparing in his criticism of institutions such as the EFCC and ICPC, describing them as “toothless bulldogs” under executive control. He called for the unbundling of power through complete institutional independence for anti-corruption agencies and charged Civil Society Organizations with resisting the politicization of the prerogative of mercy, whereby convicted individuals are pardoned on the basis of political affiliation.

Further enriching the academic discourse, he introduced the “Onion Metaphor” to illustrate corruption as a multi-layered phenomenon; one that demands not only institutional autonomy but also a profound moral rebirth to dismantle.

The lecture concluded with a deeply personal call for Probity.

Reflecting on his own academic journey to the rank of Professor, he attributed his success to integrity and probity. He challenged the university community to serve as the conscience of the nation, warning that “education without character is the greatest threat to democracy.”

Corruption Vs Corruption transcends the boundaries of an inaugural lecture; it is a mirror held up to the conscience of every Nigerian.

— Abdulkadir Bin ABDULMALIK

abdulmalikabdulkadir@gmail.com