By Daniel Adaji

Hajia Bintu Ali, a 53-year-old mother of ten, fled to the Abuja Area One Internally Displaced People (IDP) camp for refuge after a deadly Boko Haram attack in her community in Gwoza local government area, Borno state.

Everyone fled for safety. Many persons were killed, and several others are missing to date. I lost my husband and three of my children. I escaped with the next available vehicle to Abuja where I decided to seek refuge in the IDP camp,” she told The Insight.

While narrating the horrors she’d experienced, Bintu also expressed concerns over her mother’s failing health. “Because of the situation I have found myself in and the loss of my children, my mother has been worried to the point that she now has high blood pressure.”

No governmental aid

In the three years she has lived in Area One, the IDP camp, she said, had not received medical supplies or any form of support from the government. “We live on the support of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and good spirited individuals.”

The millions of refugees across the world who are forced to flee their homes comprise the most vulnerable groups in need of protection. But one major challenge they face in IDP camps is the availability of food and drugs.

Many of the children here are sick and hungry. We are not sure of daily bread

“Many of the children here are sick and hungry. We are not sure of daily bread. Sometimes, when donors come around to support, we share whatever they supply among ourselves, but it is not enough because these people don’t come here every day,” she said.

Bintu currently lives in a storage facility provided by the chairman of the camp, who she calls a “good-spirited man”, after her shed was destroyed by the wind and she was unable to put another one together.

“When the camp chairman saw my plight, he decided to provide a space for me and my family in the store. But because of the cold, I became asthmatic. Each injection I take is ₦1,500, and I have to go to Kabusa [a nearby community] to get one whenever I have the money,” she said.

Like many other IDPs, Bintu prays that one day she can return to her home. In the meantime, she called out to the Nigerian government and other individuals for help as “there are other people with worse conditions than me”.

My son has bad eyesight. We don’t have baby food, and there is no drug or any form of treatment here

Baby Yaro (not his real name) was born in the IDP camp. When The Insight visited his family’s shed, he was being breastfed by his mother. Less than a year old, he looked pale and uncoordinated due to malnutrition. Unable to hold up his head, his mother had to provide support to his back to enable him to sit up.

“My son has bad eyesight. We don’t have baby food, and there is no drug or any form of treatment here. I manage to give him breast milk as food and, whenever support comes from outside, we thank God,” she said.

Area One IDP Camp, Abuja

There are at least four IDP camps situated within Abuja, Nigeria’s capital: Lugbe, Area One, New Kuchingoro, and Kuje.

The Durumi IDP camp is situated in Area One, at the end of some very twisting and tortuous roadways. The street is littered with innocent children from the IDPs in search of daily bread. Some run around with their mates, playing happily despite their bloated bellies, pale eyes and dirty skin.

At the entrance of the camp is a borehole, the only source of potable water accessible to IDPs who contribute ₦10 for fuel. Nearby is the camp’s clinic, which has no medical practitioners on ground, and where the only available drug at the clinic is Paracetamol for pain relief.

“I have been working here for some years now. The work is so demanding, and there hasn’t been any form of support from the government. Most times when people fall sick here, they are helpless. We sometimes get donations of food and drugs from NGOs and individuals but the last time we received drugs in this clinic was over 8 years ago. The people do menial jobs and the young men among them take to Okada business. This is how some of them survive here. We don’t have child delivery facilities here,” Isah Umar, the officer in charge of the clinic, told The Insight.

The work is so demanding, and there hasn’t been any form of support from the government

Within the camp, different sheds house hundreds of people, each shed looking like an animal pen. The available sanitary systems are in terrible condition, leaving most of the IDPs resorting to open defecation due to non-availability of functionary toilets. Lacking a proper sewage disposal system, water from the bathrooms flows through the compound, polluting the air with a foul smell.

The camp also has a general kitchen which gives no sign that any cooking activities have taken place in days.

The classroom block consists of four rooms which can only offer about 100 out-of-school children access education by volunteers who assist in teaching. They are poorly furnished with no chairs for the pupils to sit at or tables to write on.

When the leadership of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Garki learned through its community service department about the IDPs in the area, they paid a visit to the facility to assist the people.

“Out of pity, they gathered basic food items such as some bags of rice, beans, some tubers of yam, noodles [and] onions, and took them to the people. Clothing [items] were not left out in the humanitarian gesture,” the Church said.

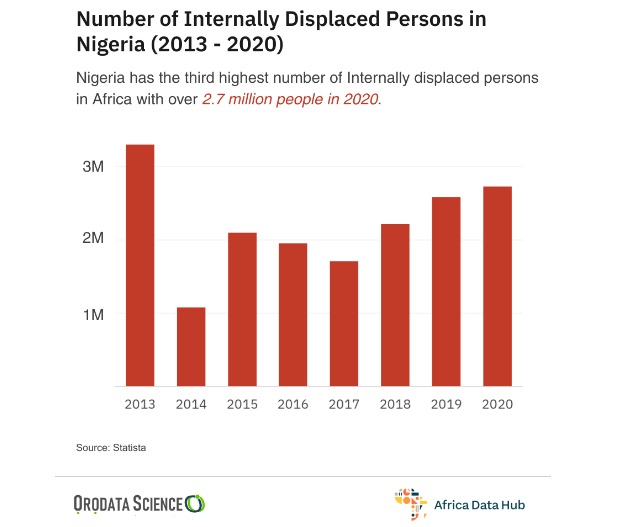

Though no official records exist, as at 2022, Statista recorded a total of 2.7 million internally displaced persons in Nigeria. In a 2015 interview with VF, Madam Fatima Ibrahim, the NEMA administrator in charge of the camp, provided information about how the camp came to be as well as the IDPs’ food system. She also revealed that many IDPs had spent longer than two years in the camp.

“We have 3,852 IDPs. They have been here for so long. Some of them have been here for two years and some of them are just arriving because of the insurgency. The number I gave you is as of January this year, which was when I came here.”

“That is not the only place for the IDPs. We have one in Lugbe, another one in Kuchigoro, and yet another in Kuje. Their feeding is basically through donations. So many people come around and render assistance in various ways. Some assist with the children’s education, health and others,” she added.

Expert opinion

According to a publication by Alice Debarre, Policy Analyst on Humanitarian Affairs at the International Peace Institute, “addressing the plight of IDPs, in particular when displacement becomes protracted, requires better implementation of the humanitarian development nexus.

“To address the longer-term needs of IDPs and support the implementation of the SDGs, internal displacement must be perceived as a long-term challenge, requiring coordinated and complementary approaches by humanitarian and development actors.

“To this end, the humanitarian and development arms of the United Nation Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, UN—OCHA and the UN Development Programme (UNDP), respectively are increasingly pursuing strategic coordination and cooperation, and the UN Secretary-General established a Joint Steering Committee in 2018 to streamline crosscutting efforts.

“Other efforts have included UN and World Bank collaboration, notably the establishment of the Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement by the United Nation High Commissioner for Refugee, UNHCR and the World Bank.

“While recent policy breakthroughs have begun trickling down to the field, and coordination between humanitarian and development actors is improving, challenges, such as a lack of comprehensive and reliable data on IDPs and separate humanitarian and development funding streams, remain.”

The is story was supported by the Africa Data Hub Community Journalism Fellowship

First published on The Insight