Before colonial maps carved Africa into angles and borders, before oil rigs rose from the Delta like metallic trees, before Abuja became a promise of modern ambition, there were rivers. The Niger and the Benue met in quiet authority, like two ancient witnesses whispering of memory. And somewhere along those banks, the Igala built a civilisation of proverbs, kingship and sacred rhythm. So the question refuses to die: if Africa walks through the pages of the Holy Bible, could one of Nigeria’s earliest footprints belong to the Igala?

The Holy Bible is not silent about Africa. Cush stands in Genesis as one of the early post flood lineages, a name many scholars associate with regions south of Egypt. Egypt itself dominates the Old Testament story, not as a footnote but as a superpower. In the New Testament, an Ethiopian official reads Isaiah on a desert road before his conversion in Acts. Africa is not an afterthought in holy scripture. It is present at the beginning and present again at the birth of the Church. The real debate is not whether Africa is there. It is how far west that ancient shadow stretches.

Serious historians will caution against romantic leaps. There is no archaeological consensus that ties the Igala directly to a named biblical patriarch. No inscription has surfaced along the Niger declaring a covenant in Hebrew script. But history in Africa has never depended solely on stone tablets. It has lived in drumbeat and dynasty, in praise poetry and royal stool. Oral tradition has been archive, library and constitution. To dismiss it entirely is to misunderstand how memory survives where paper does not.

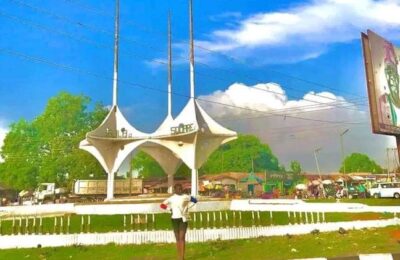

The Igala kingdom, centred at the confluence of the Niger and Benue, developed a structured kingship under the Attah, elaborate spiritual systems, and a moral code woven into communal life. Their cosmology speaks of a supreme creator. Their proverbs elevate patience, justice and reverence. These are not uniquely biblical ideas, but they echo themes familiar to readers of Genesis and Proverbs. When John Mbiti wrote that Africans are notoriously religious, he was not romanticising the continent. He was observing a worldview in which the sacred saturates the ordinary.

Geography complicates and enriches the discussion. Trade routes connected the Nile Valley to West Africa long before European arrival. Trans Saharan networks moved salt, pepper, animals, gold, ideas and belief. Islam reached Hausaland centuries before colonial rule. Christianity, in different forms, has ancient roots in North and East Africa. Cultural exchange was not a modern invention. It is conceivable that stories, symbols and spiritual frameworks travelled gradually westward, absorbed and reshaped along the way. That possibility does not prove an Igala patriarch in Genesis, but it keeps the conversation open.

What is at stake here is not merely ethnic pride. It is expository ownership. For generations, Africans encountered the Bible as a holy book delivered by missionaries who sometimes implied that civilisation arrived with the cross. Yet long before European ships anchored off West African coasts, societies like the Igala had law, kingship and metaphysical imagination. Lamin Sanneh argued that Christianity is uniquely translatable, capable of taking root in local soil without losing its essence. If that is true, then Africa is not a late guest at the biblical table. It is fertile ground that recognises familiar truths.

Sceptics are right to demand evidence. Faith is not strengthened by fragile claims. But neither is identity strengthened by silence. To ask whether the first Nigerian in the Bible might have been Igala is to challenge the inherited assumption that sacred history belongs elsewhere. It forces a re reading of maps. It pushes Nigerians to see scripture not only as imported text but as intersecting story.

There is also a psychological dimension. Nations emerging from colonial distortion often search for anchors deeper than the nineteenth century. The Igala story, like many indigenous narratives, offers continuity. It reminds Nigerians that they were not blank slates awaiting foreign inscription. Even if no verse in Genesis names an ancestor from the Niger Benue confluence, the moral imagination of the people suggests a long dialogue with the divine.

In the end, the claim may remain unproven. No responsible scholar would stamp it as settled fact. Yet the question itself performs important work. It restores Africa to the foreground of sacred history. It insists that rivers in Kogi are not spiritually inferior to rivers in Mesopotamia. It invites Nigerians to read the Holy Bible with both reverence and confidence.

Perhaps the more honest conclusion is this: Africa has always been inside the story, even when readers forgot to look. Whether or not the Igala were the first Nigerians to walk the pages of scripture, they stand as evidence that faith did not arrive on an empty shore. It met people already searching, already worshipping, already telling stories about the origin of life and the authority of heaven.

Like an ancient baobab whose roots run deeper than the eye can see, identity is not always visible on the surface of text. Sometimes it must be traced through memory, migration and meaning. And in that search, Nigeria may discover that its spiritual heritage is older, richer and more intertwined with the biblical world than it once dared to imagine.

– Inah Boniface Ocholi writes from Ayah – Igalamela/Odolu LGA, Kogi state.

08152094428 (SMS Only)