History teaches that hunger is never merely an agricultural failure; it is a moral and political one. Nations collapse not because they lack land or people willing to farm it, but because policy forgets whom agriculture is meant to serve. In Nigeria’s current struggle with food prices and food production, this lesson could not be more urgent.

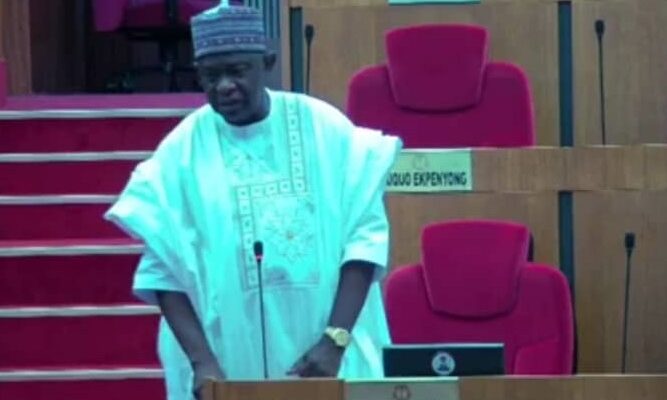

It was against this backdrop that Distinguished Senator Sunday Steve Karimi, representing Kogi West, rose on the floor of the Nigerian Senate and spoke with a clarity that echoed the wisdom of two of the world’s most respected agricultural thinkers: M.S. Swaminathan and George Washington Carver. Like them, Senator Karimi spoke not in slogans, but in principles rooted in humanity, productivity, and justice.

He began where every honest discussion of food must begin—with insecurity. Farmers across Nigeria, he noted, are increasingly unable to access their farms. Fields lie idle not because farmers are lazy, but because fear has become a daily companion to agriculture. This insecurity undermines production, weakens supply, and sets the stage for scarcity. No nation can speak seriously about food security while its farmers are unsafe.

But Senator Karimi did not stop there. He turned the Senate’s attention to the lived reality of consumers. He reminded the chamber of a painful recent memory: when a 50kg bag of rice climbed toward ₦180,000. At that moment, food ceased to be a commodity and became a crisis. Families skipped meals. Salaries dissolved before the middle of the month. Hunger became political, not by design, but by consequence.

As expected, government was blamed. Yet when government intervened—allowing temporary importation to stabilize prices—relief followed. Prices fell. Markets adjusted. Ordinary Nigerians felt a measure of breathing space. Then, almost immediately, a familiar paradox emerged: complaints that falling prices were hurting farmers.

Senator Karimi named this contradiction with rare honesty. When prices rise, government is condemned. When prices fall, government is condemned. In both scenarios, the suffering of the ordinary citizen is treated as collateral damage in a policy tug-of-war.

This, he argued, is neither balance nor wisdom.

Here his thinking mirrors that of M.S. Swaminathan, who consistently warned that food policy must be guided by equity, not just output. Swaminathan insisted that agricultural success is meaningless if it leaves large segments of the population hungry. Senator Sunday Karimi echoed this ethos when he stated unequivocally that prices must not be allowed to rise endlessly in the name of protecting farmers.

“I believe encouraging prices to go down is the best,” he said.

This was not economic ignorance; it was moral clarity. George Washington Carver, working with poor farmers in the American South, understood that agriculture must lift both producer and consumer. He taught that prosperity comes from innovation, diversification, and support—not from scarcity imposed on the poor. Senator Karimi’s argument aligns perfectly with this tradition.

He was careful to emphasize that he is not anti-farmer. On the contrary, he argued passionately that farmers must be supported—but in the right way The path to farmer prosperity, he said, lies in incentives, equipment, quality seedlings, and productive inputs. In other words, raise yields, lower costs, and improve efficiency.

This distinction is crucial. Artificially high food prices do not strengthen agriculture; they simply redistribute pain. They punish consumers while masking structural weaknesses in production. Senator Karimi rejected this approach outright. He insisted that Nigeria must subsidize productivity, not hunger.

This philosophy places him firmly within a lineage of agricultural humanists. Like Swaminathan, he sees farmers as central to national survival—but not as a privileged class whose welfare must come at the expense of the poor. Like Carver, he believes that smart support, innovation, and investment can make farming profitable without making food unaffordable.

For the people of Kogi West, this intervention was not theoretical. It spoke directly to the realities of daily life: the civil servant whose salary no longer matches market prices, the market woman whose customers buy less each week, the farmer who wants fair returns but also belongs to a community that must eat.

In an era where political debate often collapses into blame and ideological extremes, Senator Karimi’s refusal to choose sides was itself an act of leadership. He acknowledged government efforts to reduce the cost of living while insisting that such efforts must be defended, refined, and sustained. Policy, he implied, must be judged not by who shouts the loudest, but by who eats at the end of the day.

This is what full-spectrum representation looks like. It is leadership that understands that food security without affordability is insecurity by another name, and affordability without sustainable farming is equally hollow. The task of governance is to hold both truths at once.

By speaking plainly for consumers without abandoning farmers, Senator Sunday Steve Karimi demonstrated a rare balance of courage and compassion. In doing so, he aligned himself with the great agricultural thinkers who understood that the true measure of a food system is not how much it produces, but how many it nourishes.

When history judges this moment, it will remember those who protected abstractions—and those who protected people. Senator Karimi has made his choice clear.

— Yusuf, M.A., PhD

For: Kogi Equity Alliance